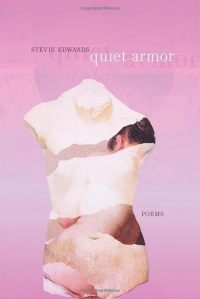

Stevie Edwards holds a Ph.D. in creative writing from University of North Texas and an M.F.A. in poetry from Cornell University. Their poems have appeared in Poetry Magazine, American Poetry Review, Crazyhorse, and elsewhere. Edwards is an assistant professor at Clemson University and the author of Sadness Workshop (Button Poetry, 2018), Humanly (Small Doggies Press, 2015), and Good Grief (Write Bloody Publishing, 2012), and Quiet Armor (Northwestern University Press, 2024). Edwards is currently Poetry Editor of The South Carolina Review. Originally a Michigander, they now live in South Carolina with their husband and a small herd of rescue pitbulls (Daisy, Tinkerbell, and Peaches).

Trinity Castle-Pollard is a creative writing major at Albion College.

Trinity Castle-Pollard: What is your personal relationship with poetry? When did you first discover a poem that resonated with you?

Stevie Edwards: When I was in the 8th grade, I started really loving reading and writing poetry. I remember a specific project where we made scrapbooks of our favorite poems in my English class, and one of my first favorite poems was “Not Waving but Drowning” by Stevie Smith, which is not why I’m named Stevie, but that was one of my first favorite poems. But in general, I was kind of an emo kid in high school, and I found poetry as an outlet. I had a lot of angst and I found it as an outlet to express myself. When I was a teenager I really wanted to be a singer-songwriter, but to be honest I’m not that good at guitar or singing, and I just started realizing I was a lot better at the writing part.

TCP: Was there a particular moment when you knew you wanted to be a poet? Was that when you realized you did not want to be a singer anymore?

SE: I loved writing when I was an undergraduate, and I was very dedicated to it, but I never really saw it as a career path until after I had graduated. I also have an economic, or econ and management major from [Albion College]. I was a weird double major, and I thought I was going to do something much more practical with my life, but when I graduated, I moved to Chicago, and I became involved with the poetry community there. I was a 22-year-old, and I realized there were all these 40-year-olds who appreciated my poetry, and getting that response from older writers kind of pushed me to want to make it more of my career path and made me think more seriously about doing an M.F.A.

TCP: Who is your favorite poet, and if you don’t have just one, who are some poets that you admire?

SE: Favorites are very hard, but there are many poets that I admire. One of my favorite contemporary writers is Natalie Diaz. Also Patricia Smith. Those are probably two, and Terrance Hayes. I’m trying to think. For slightly older-school writers, I love Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton, and Muriel Rukeyser.

TCP: Are there any specific forms of poetry you hope to do more with going forward, anything you want to experiment with?

SE: Yeah, so I’ve been thinking a lot about what’s called hermit crab poetry, which is where you use forms borrowed from other aspects of life to write in, like writing a poem that’s like a bingo card, or writing a poem that’s like a grocery list. I think there’s something really appealing about borrowing these different writing forms that are part of our daily life and using them in poetry.

TCP: Would the bingo card ones have different words in each box, or would they spell things in different ways?

SE: So, I’ve seen one bingo card poem. I haven’t written one yet, but my friend Lauren Brazeal has one. Hers was something about being a homeless teenager and trying to find dinner. All the different squares were different options for how you might find dinner, so it might be a dumpster. There would be some slots that said sleep for dinner, or some slots that said things like leftovers from Panda Express. I’m making things up—I don’t remember exactly what’s on it, but it was about the luck of falling into getting some food. One of my former professors, Jill Talbot, has this personal essay that is in the form of a syllabus, and it’s about the start of a semester where her life fell apart. It uses the form of a syllabus to tell that story.

TCP: Do you write poems similar to the ones you enjoy reading, or do you prefer a different format when you are not the one writing them?

SE: I tend to write pretty narrative poetry, and I read narrative poetry, but I read very broadly. I’ll read things that are much more experimental than what I write sometimes. I love reading Diane Seuss, and I write nothing like Diane Seuss. So I definitely love reading poems that have the same aesthetic as me. I like to read broadly, and sometimes I think it pushes me in interesting directions when I read something that is totally different from myself.

TCP: Did any of your poems feel like they needed to be written? Was there ever an idea that refused to leave your brain until you put it to paper.

SE: Yes, a lot of my collection Quiet Armor is about trauma I experienced as a young person. For a lot of those poems, I felt the need to sort of tell my story, to get it down, how I experienced it, and there was something terrifying about that, but there’s also something freeing about it, I think, in that it helped me to process things I believe.

TCP: Does presenting your work come naturally to you? If not, how did you gain the confidence needed to read poetry in front of a crowd of people?

SE: The answer is no, it does not come naturally to me. I have terrible stage fright, I remember when my first book came out. I was very young—I was 24, I think. It was with a press that’s known for performance poetry called Write Bloody Publishing, and they’re great, but they had in my contract that I had to do at least 20 readings of the book in the first year. I was excited but terrified. The real answer was I just had to make myself do it over and over until it stopped feeling so terrible.

TCP: Has it stopped feeling terrible yet?

SE: I still get a little butterflies, but it’s a lot better.

TCP: Is there anything about being published you wish you had known when you started submitting your work?

SE: I wish I had known that so many online literary magazines would disappear. I have all these things on my CV where I have to put in brackets “now defunct.” When I started out, I wasn’t really looking towards the longevity of the magazines, I was just submitting stuff where I thought they were cool. I might have thought a little more about longevity. I guess as far as other stuff—I’m trying to think of how to put this—I had some issue with my second book being published in that the publisher was very small and had understandable health problems, but it really affected the way my book got out into the world and the ability to promote it. I think if I went back in time, I might have made a different choice there, so that the book would have gotten into more bookstores and been more widely read.

TCP: Have you found it easier publishing with different companies?

SE: My last two experiences have been really good. My current book is out on the Northwestern University Press. They were very professional and good to work with. They’ve been really excellent. And I had a cha[book come out before that in 2018, with Blood and Poetry and they are a promotion machine. I don’t know how they do what they do, but they’re amazing at promoting their books.

TCP: Do you have any tips for getting around writer’s block when you really know you need to write something but no ideas are coming?

SE: Isn’t that always everyone’s problem? This might not sound like a great piece of advice, but I find taking showers helps to reset my brain, also going for walks, and good snacks. Also, if I’m really stuck, a lot of times the answer is that I need to be reading more. So a lot of times, if I’m stuck, I’ve only been reading from what I’m teaching, and I haven’t been reading for fun.

TCP: Is there any particular book that’s really inspired you when you were trying to write poetry?

SE: I’m trying to think of what I’ve been obsessed with lately. One book that I’ve read, probably not a thousand times,but a lot of times, is Crush by Richard Siken. I would say that’s one I can always come back to when I’m stuck.

TCP: What advice would you give young poets when it comes to allowing themselves to be vulnerable in poetry they know others will read?

SE: I think it’s a tricky thing. If vulnerability is something that you value and you want, I think it’s important to give yourself permission to do that. But I think it’s also important to know your own boundaries. Earlier in my career, I put out some poems that were too tender feeling. I think they were good poems, but I don’t know if it was actually good for me as a person. I felt so much anxiety about them being published. But at the same time, I do think there is power in vulnerable work, and that it can create a space where other people feel seen, people who’ve gone through similar experiences can be seen, and also it gives other people an opportunity for empathy with experiences they might not have really thought about. So I do believe in the power of vulnerable work, and I think it’s important, but at the same time it’s also important to take care of yourself. It’s a balance. And I’m not saying it’s an easy balance to create.

TCP: Is there anything else we didn’t talk about that you would like to share?

SE: I guess one thing I could talk about is that I’ve done a lot of editorial work in publishing, and I’ve found that editing other people’s books and editing literary magazines has helped me really figure out my own voice and where I fit into things. The wide reading you’re forced to do when you’re reading a submission pile of several hundred poetry manuscripts makes you consider other aesthetics and really figure out where you fit into things.

TCP: Have you had any luck finding writing groups since you’ve graduated from college where you can do the workshop process that is so incredibly helpful?

SE: I did an M.F.A., and I did a Ph.D., which are both programs that involve workshops, and in order to find that kind of community outside of that, I’ve done some summer programs. Last summer, I was at the Vermont Studio Center which involved both visual artists and creative writers. I got to collaborate with some creative writers there. The summer before, I did something called Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and that involved a workshop element. But, in my daily home life, I don’t have much of a workshop environment. I wish I did. I wish I had better news there. I’m a little isolated where I’m at currently

TCP: You’re coming to speak at a poetry class at Albion College. How does it feel to come back to the place you learned your craft, where you’re now seen as an authority on the subject?

SE: To be honest, it makes me very nostalgic, and a little—this might sound corny—proud. I really loved my English education at Albion, and I’m not just saying that because I’m a representative here, but I really loved the English classes I took at Albion. I loved my poetry classes that I took here, and other creative writing classes. It’s really meaningful to get to come back and to feel like an authority. It’s meaningful. I’ve given talks at other colleges before, but this one—There was this worry yesterday that the weather would cancel my flights. And I was like, “No, not this one.” Because it does matter to me. I mean all readings matter to me, but this one has a special place in my heart.